Patrick Henry & the Stamp Act (Historical Reprint)

Historical article reprinted from the book "American Heroes & Leaders" written by Wilbur Fisk Gordy in 1907.

After the close of the Last French War, England was heavily in debt. As this debt had been incurred largely in defense of the English colonies in America, George III, King of England, believed that the colonies should help to carry the burden. Moreover, as he intended to send them a standing army for their protection, he deemed it wise to levy upon them a tax for its support.

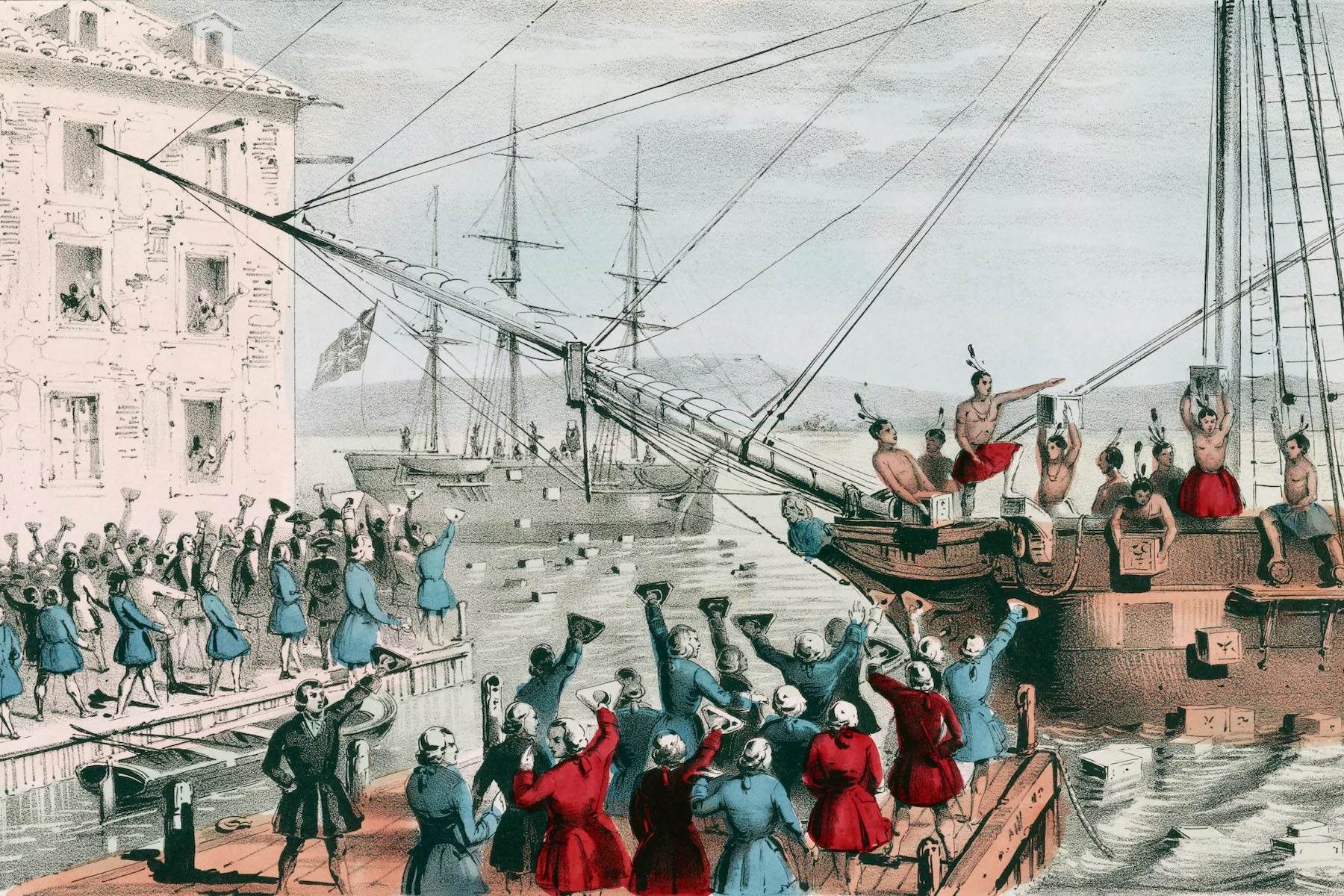

Parliament, therefore, which was composed largely of the King's friends, ready to do his bidding, passed a law called the Stamp Act. This required the colonists to use stamps upon their newspapers and upon legal documents, the price of stamps ranging from a half-penny to twelve pounds. The King thought this tax would be just because it would fall upon all the colonists alike.

But the colonists were of a different mind; for England had not fought the Last French War so much to defend them as to protect her own trade. Besides, they had already paid a reasonable share of the war expenses, and had furnished a fair proportion of soldiers for battle. They had always given their share toward the expenses of their defense, and were still willing to do so. If the King would ask them for a definite sum, they would raise it through their Colonial Assemblies. But they strongly objected to any English tax.

These Colonial Assemblies were composed of men who represented the colonists and made laws for the colonists. Therefore, the colonists were willing to pay any taxes levied by the Assemblies. As free-born Englishmen they objected to paying taxes levied by Parliament, which did not represent them. Parliament might levy taxes upon the people of England, whom it did represent. But only the Colonial Assemblies could tax the colonists, because they alone represented the colonists. In other words, as James Otis in a stirring speech had declared, there must be "No taxation without representation".

George III could not understand the feelings of the colonists, and he had no sympathy with their views. His mother had said to him when he was crowned, "George, be King", and this advice had pleased him. For he was willful, and desired to have his own way as a ruler. Thus far he had shown little respect for the British Parliament, and he felt even less for Colonial Assemblies. Certainly, if he was to rule in his own way in England, he must compel the obedience of the stubborn colonists in America. The standing army which the King wished to send to America was designed not so much to protect the colonies as to enforce the will of the King, and this the colonists knew. They, therefore, opposed with bitter indignation the payment of taxes levied for the army's support.

Patrick Henry was one of many who were willing to risk everything in their earnest struggle against the tyrannical schemes of King George. Patrick Henry was born in 1736 in Hanover County, Virginia. His father was a lawyer of much intelligence, and his mother belonged to a fine old Welsh family. As a boy, Patrick's advantages at school were meager, and even these he did not appreciate. Books were far less attractive to him than his gun and fishing rod. With these he delighted to wander through the woods searching for game, or to sit on the bank of a stream fishing by the hour. When outdoor sports failed, he found delight at home in his violin.

When he was fifteen years old, his father put him into a country store, where he remained a year. He then began business for himself, but he gave so little attention to it that he soon failed. He next tried farming, and afterward storekeeping again, but without success.

At length he decided to practice law, and after six months of study, applied for admission to the bar. Although he had much difficulty in passing the examination, he had at last found a vocation which suited him, and he did well in his law practice. In 1765 he traveled to Williamsburg, soon after the passage of the Stamp Act by the English Parliament, to attend the session of the Virginia House of Burgesses, of which he had been elected a member.

We get a vivid picture of our hero at this period of his career as he rides on horseback toward Williamsburg, carrying his papers in his saddlebags. John Esten Cooke says of him, "He was at this time just 29, tall in figure, but stooping, with a grim expression, small blue eyes which had a peculiar twinkle, and wore a brown wig without powder, a peach-blossom coat, leather knee-breeches, and yarn stockings."

There was great excitement in Williamsburg, and it was a time of grave doubt. What should be done about the Stamp Act? Should the people of Virginia tamely submit to it and say nothing? Should they urge Parliament to repeal it? Or should they cry out against it in open defiance?

Most of the members were wealthy planters, men of dignity and influence. These men spoke of England as the "Mother" of the colonies, and were so loyal in their attachment that the idea of war was hateful to them. Certainly, the thought of separation from England they could not entertain for a moment. But Patrick Henry was eager for prompt and decisive action. Having hastily written, on a blank leaf taken from a law-book, a series of resolutions, he rose and offered them to the assembly. One of these resolutions declared that the General Assembly of the colony had the sole right and power of laying taxes in the colony.

A hot debate followed, in the course of which Patrick Henry, ablaze with indignation, arose and addressed the body. His speech closed with these thrilling words, "Caesar had his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell, and George the Third may profit from their example"

"Treason! Treason!", shouted voices from the stormy assembly.

Pausing a moment in a fearless attitude, the young orator calmly added, "If this be treason make the most of it."

The resolutions were passed.

It was a great triumph for the young orator, who now became the "idol of the people". As he was going out the door at the close of the session, one of the plain people gave him a slap on the shoulder, saying, "Stick to us, old fellow, or we are gone!"

The note of defiance sounded by Patrick Henry vibrated throughout America, and encouraged the Colonists to unite against the oppressive taxation imposed upon them through the influence of the stubborn and misguided King George.

But the English people as a whole did not support the King. Many of them, among whom were some of England's wisest statesmen, believed he was making a great mistake in trying to tax the Americans without their consent. Said William Pitt, in a stirring speech in the House of Commons, "Sir, I rejoice that America has resisted. Three* million people so dead to all the feelings of liberty as voluntarily to submit to be slaves, would have been fit instruments to make slaves of all the rest." (* The actual number would have been closer to two million.)

In the ten years following the passage of the Stamp Act, events in America moved rapidly. The colonial merchants refused to import goods so long as the Stamp Act was in effect. Their action caused the merchants, manufacturers, and shipowners in England to lose money heavily. These merchants and shipowners begged Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. Parliament did repeal it one year after its passage.

Ten years after Patrick Henry's eloquent speech at Williamsburg against the Stamp Act, the people of Virginia were again deeply aroused; for King George, acting through Parliament, had sent 3,000 soldiers to Boston to force her unruly people and those of Massachusetts to obey certain of his commands. Virginia having given her hearty support to the people of Massachusetts, the royal Governor of Virginia drove the Colonial Assembly away from Williamsburg. But the people of Virginia, resolute in defense of their rights, elected a convention of their leading men, who met at old St. John's Church in Richmond. Excitement was widespread, and thoughtful men grew serious at the war-cloud growing blacker every hour.

Virginians had already begun to make preparations to fight if they must. But many still hoped that the disagreements between the Americans and King George might be settled, and therefore believed that they should act with great caution. Patrick Henry thought differently. He was persuaded that the time had come when talk should give place to prompt, energetic, decisive action. The war was at hand. It could not be avoided. The Americans must fight, or tamely submit to be slaves.

Believing these things with all the intensity of his nature, he offered a resolution that Virginia should at once prepare to defend herself. Many of the leading men stoutly opposed this resolution as rash and unwise.

At length Patrick Henry arose, his face pale and his voice trembling with deep emotion. Soon his stooping figure became erect. His eyes flashed fire. His voice rang out like a trumpet. As he continued, men leaned forward in breathless interest of his words:

"We must fight! I repeat it, sir, we must fight! An appeal to arms and to the God of Hosts is all that is left us! They tell us, sir, that we are weak; unable to cope with so formidable an adversary. But when shall we be stronger? Will it be the next week, or the next year? Will it be when we are totally disarmed, and when a British guard shall be stationed in every house? Shall we gather strength by irresolution and inaction? Shall we acquire the means of effectual resistance by lying supinely on our backs and hugging the delusive phantom of hope, until our enemies shall have bound us hand and foot? Sir, we are not weak, if we make a proper use of the means which the God of nature hath placed in our power... There is no retreat, but in submission and slavery! Our chains are forged! Their clanking may be heard on the plains of Boston! The war is inevitable - and let it come! I repeat it, sir, let it come!"

"It is in vain, sir, to extenuate the matter. Gentlemen may cry peace, peace - but there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the North will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God!"

"I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!"

This speech made a deep impression not only in Virginia but throughout the colonies. The next month the war began at Lexington and Concord. A little later Patrick Henry was made commander-in-chief of the Virginia forces, and later still was elected Governor of Virginia.

At the age of 58 he retired to an estate in Charlotte County called "Red Hill", where he lived a simple life. He died in 1799. His influence in arousing the people of Virginia and of the other colonies to a sense of their rights as freemen cannot easily be measured. Without doubt his impassioned oratory played a most important part in shaping the course of events which resulted in the Revolutionary War.