Daniel Webster: Defender and Expounder of the Constitution

Historical article reprinted from the book "American Heroes & Leaders" written by Wilbur Fisk Gordy in 1907.

Daniel Webster was born among the hills of New Hampshire, in Salisbury (now Franklin), in 1782, the son of a poor farmer and the ninth of ten children. As Daniel was a frail child, not able to work much on the farm, his parents permitted him to spend much time in fishing, hunting, and roaming at will over the hills. Thus he came into close touch with nature, and gained much knowledge which was useful to him in later years. It was his good fortune to have as a companion on these out-door excursions an old English soldier and sailor then living in a small house on the Webster farm. The two friends, so far apart in age, were good comrades, and were often seen walking together along the streams. The old soldier entertained his young listener with many thrilling tales of adventure on land and sea, and the boy read to his friend from books which the old man liked well.

Daniel's father had also been a soldier, having served in Indian wars and in the Revolution, and related many interesting experiences to his son. One which always appealed to young Daniel was the account of a meeting, years before, with General Washington at the time when Arnold was found to be a traitor. In this interview Washington had taken Webster's hand and, looking seriously into his face, had said, "Captain Webster, I believe I can trust you." This expression of confidence by the general to his subordinate stirred the boy's imagination.

In these ways did his patriotism receive a great stimulus. An incident which occurred when he was only eight years old illustrates the seriousness of his mind. Having seen at a store near his home a small cotton handkerchief with the Constitution of the United States printed on it, he gathered up his small earnings to the amount of 25-cents and eagerly secured the treasure. From this remarkable copy he learned the Constitution word for word, so that he could repeat it from beginning to end.

Of course this was an unusual thing for an eight-year-old boy to do, but the boy himself was unusual. He spent much of his time poring over books. They were few in number, but of good quality, and he read them over and over again until he made them a part of himself. It was a pleasure to him to memorize fine poems also, and noble selections from the Bible, for he learned easily and remembered well what he learned. In this way he stored his mind with the highest kind of truth.

Naturally his father was proud of his boy and longed to give him a good education. One day, when Daniel was only 13 years-old, they were at work together in the hay field, when a college-bred man, also a member of Congress, stopped to speak with Mr. Webster. When the stranger had gone his way, Mr. Webster expressed to his son deep regret that he himself was not an educated man, adding that because of his lack of education he had to work hard for a very small return.

"My dear father," said Daniel, "you shall not work. Brother and I will work for you, and will wear our hands out, and you shall rest." Then Daniel, whose heart was tender and full of deep affection, cried bitterly.

"My child," said Mr. Webster, "it is of no importance to me. I now live but for my children. I could not give your elder brothers the advantage of knowledge, but I can do something for you. Exert yourself, improve your opportunities, learn, learn, and when I am gone you will not need to go through the hardships which I have undergone, and which have made me an old man before my time."

These words show the earnest purpose of the father. The next year the boy, now 14, was sent to Phillips Exeter Academy. The principal began Daniel's examination by directing him to read a passage in the Bible. The boy's voice was so rich and musical and his reading so intelligent that he was allowed to read the entire chapter and then admitted without further questioning. This was only one illustration of his marvelous power as a reader. Teamsters used to stop at the home farm in order to hear that "Webster boy" as they called Daniel, read or recite poetry or verses of Scripture.

The boys he met at the academy were mostly from homes of wealth and culture. Some of them were rude and laughed at Daniel's plain dress and country manners. Of course the poor boy, whose health was still weak and who was by nature shy and independent, found such treatment hard to bear.

But he studied well, and soon commanded respect because of his high rank. One of his school duties, however, he found impossible to perform, and that was to stand before the school and declaim. He would carefully memorize and practice his declamation, but, when called on to speak, he could not rise from his seat and go upon the platform. During the nine months of his stay in the academy, he failed to overcome his deficiency in declaiming.

After leaving this school he studied for six months under Dr. Woods, a private tutor, who prepared him to enter Dartmouth, at the age of 15.

Although he proved himself to be a youth of great mental power, he did not take high rank in scholarship. But he continued to read widely and thoughtfully, and acquired much valuable knowledge which he used with great clearness and force in conversation or debate. While in Dartmouth, he overcame his inability as a declaimer, and gave striking evidence of the oratorical power for which he afterward became so famous.

After spending two years in Dartmouth, Daniel begged his elder brother Ezekiel to join him there. But Ezekiel was needed at home, for their father, who was now 60 years-old, was in poor health and had even at that age to work hard to feed and clothe his family. He had found it necessary to mortgage the farm to send Daniel to college. How could he send Ezekiel, too? It seemed foolish to think of doing so. But when Daniel urged such a course and agreed to help by teaching, the matter was arranged.

After graduation Daniel taught for a year and earned the money he had promised Ezekiel. The following year he studied law and in due time was admitted to the bar. As a lawyer he was successful, his income sometimes amounting to $20,000 in a single year. But he could not manage his money affairs well, and no matter how large his income he was always in debt. This unfortunate state of affairs was owing to a reckless extravagance, which he displayed in many ways.

Indeed, Webster was a man of such large ideas that of necessity he did all things on a large scale. It was vastness that appealed to him. And this dominating force in his nature explains his idea of nationality and his opposition to State Rights. He was too large in his views of life to limit himself to his State at the expense of his country. To him the Union stood first and the State second, and to make the Union great and strong became a ruling passion in his life.

Webster's magnificent reach of thought and profound reverence for the Union is best expressed in his speeches. The most famous one is his brilliant "Reply to Hayne."

Senator Hayne, of South Carolina, had delivered an able speech, in which he put the authority of the State before that of the Union, and said that the Constitution supported that doctrine. Webster, then a senator from Massachusetts, had but one night to prepare an answer. But he knew the Constitution by heart, for he had been a close student of it since the days of childhood, when he had learned it from the cotton handkerchief.

Senator Hayne's masterly speech caused many people to question whether even Daniel Webster could answer his arguments, and New England men especially, fearing the dangerous doctrine of State Rights, awaited anxiously the outcome. When, therefore, on the morning of January 26, 1830, Mr. Webster entered the Senate Chamber to utter that memorable reply, he found a crowd of eager men and women waiting to hear him.

"It is a critical moment," said a friend to Mr. Webster, "and it is time, it is high time, that the people of this country should know what this Constitution is."

"Then," said Webster, "by the blessing of Heaven they shall learn, this day, before the sun goes down what I understand it to be."

Nationality was Webster's theme, his sole purpose being to strengthen the claims of the Union. For four hours he held his audience spellbound while he set forth with convincing logic the meaning of the Constitution. The great orator won an overwhelming victory. Not only were many of his hearers in the Senate chamber that day convinced, but loyal Americans all over the country were inspired with more earnest devotion to the Union.

His last words "Liberty and Union! One and inseparable, now and forever" electrified his countrymen and became a watchword of national progress.

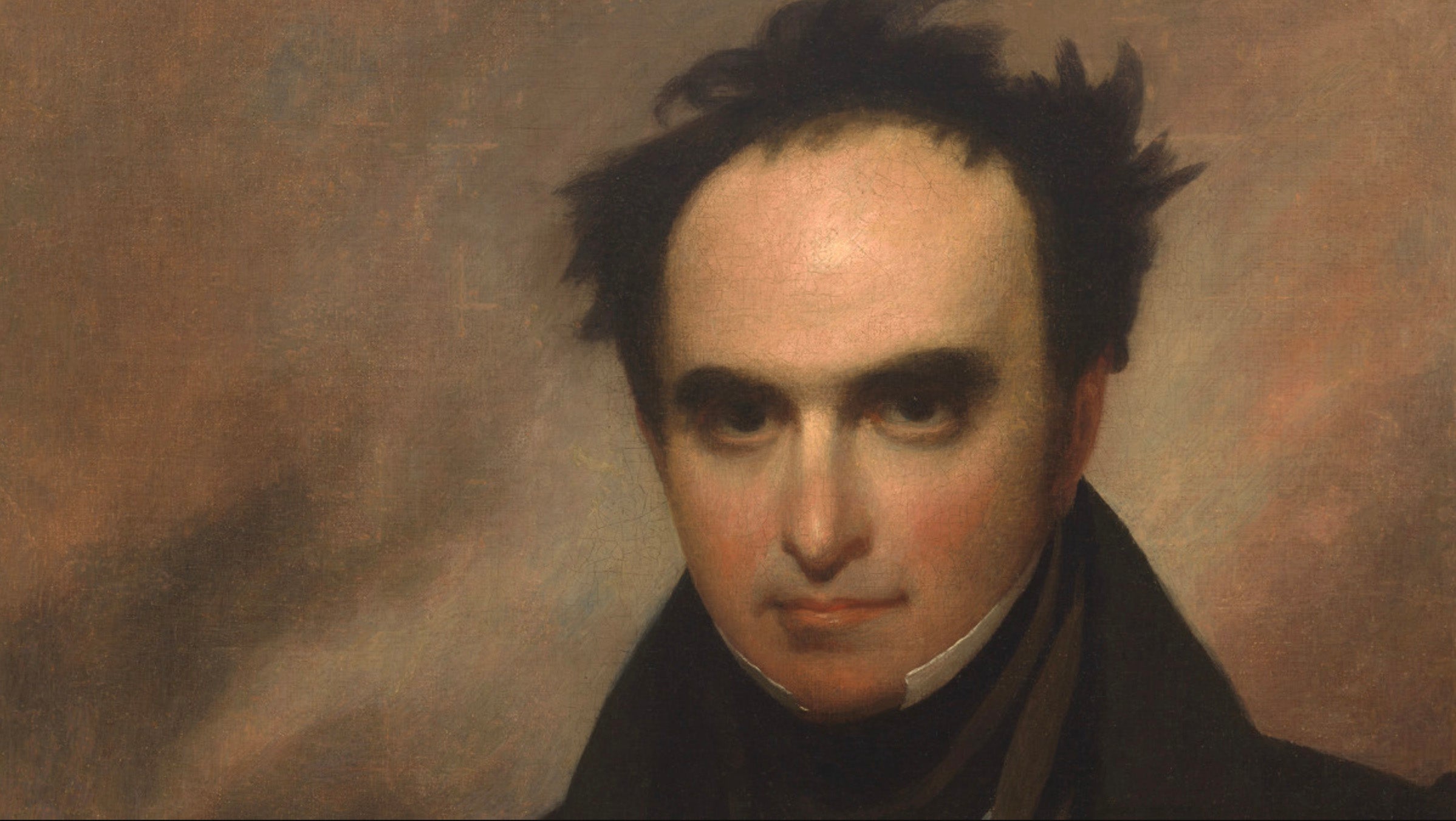

Webster's power as an orator was enhanced by his remarkable physique. His striking personal appearance made a deep impression upon everyone who saw or heard him. One day when he was walking through one of the streets of Liverpool a laborer said of him, "There goes a king!" On another occasion Sydney Smith exclaimed, "Good heavens! He is a small cathedral by himself." He was nearly six feet tall. He had a massive head, a broad, deep brow, and great coal-black eyes, which once seen could never be forgotten.

To the day of his death he showed his deep affection for the flag, the emblem of that Union which had inspired his noblest efforts. During the last few weeks of his life, troubled much with sleeplessness, he used to watch the stars, and while thus occupied his eyes would often fall upon a small boat of his which floated in plain view of his window. On this boat he had a ship lantern so placed that in the darkness he could see the Stars and Stripes flying there. The flag was raised at six in the evening and kept flying until six in the morning to the day of Daniel Webster's death, which took place in September, 1852. On looking at the dead face a stranger said: "Daniel Webster, the world without you will be lonesome."